Dewey and Montessori

Scientific pedagogy is a way of helping children with

learning in school. Schools were at first furnished with the long, narrow

benches upon which the children were crowded together. Then came science and

perfected the bench. In this work much attention was paid to the recent

contributions of anthropology. The age of the child and the length of his limbs

were considered in placing the seat at the right height. The distance between

the seat and the desk was calculated with infinite care, in order that the child's

back should not become deformed, and, finally, the seats were separated and the

width so closely calculated that the child could barely seat himself upon it,

while to stretch himself by making any lateral movements was impossible. This

was done in order that he might be separated from his neighbor. Freedom, like

physical education, is also very important in education, giving time to rest

the mind.

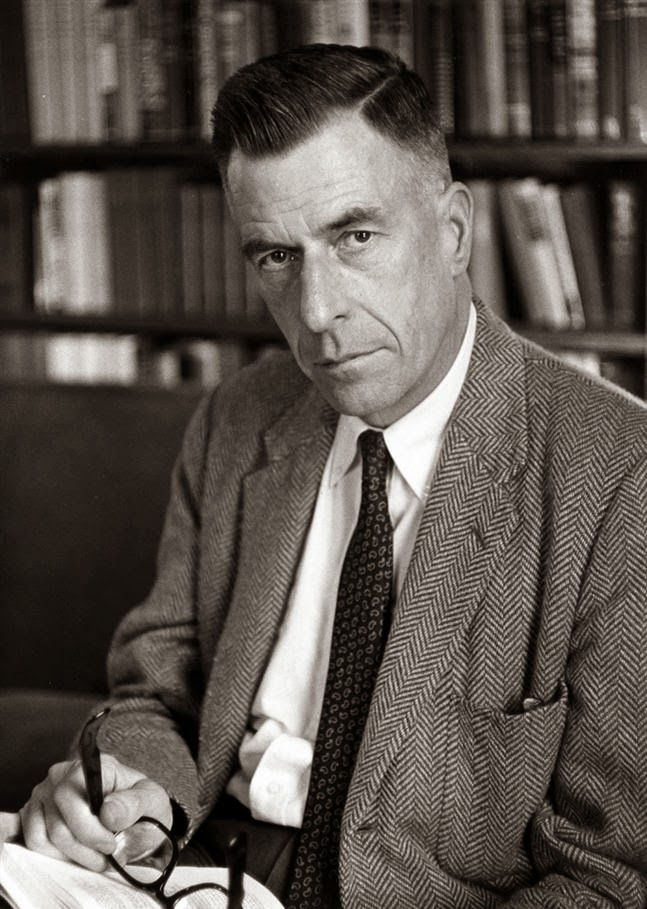

Dewey was born in Burlington, Vermont, to a family of modest

means. Like his older brother, Davis Rich Dewey, he attended the University of

Vermont, from which he graduated in 1879. In 1894 Dewey joined the newly

founded University of Chicago where he developed his belief in Empiricism,

becoming associated with the newly emerging Pragmatic philosophy. His time at

the University of Chicago resulted in four essays collectively entitled Thought

and its Subject-Matter, which was published with collected works from his

colleagues at Chicago under the collective title Studies in Logical Theory.

During that time Dewey also initiated the University of Chicago Laboratory

Schools, where he was able to actualize the pedagogical beliefs that provided

material for his first major work on education, The School and Social Progress.

Disagreements with the administration ultimately caused his resignation from

the University, and soon thereafter he relocated near the East Coast. In 1899,

Dewey was elected president of the American Psychological Association. From

1904 until his retirement in 1930 he was professor of philosophy at both

Columbia University and Columbia University's Teachers College. In 1905 he

became president of the American Philosophical Association. He was a longtime

member of the American Federation of Teachers.